Over two decades after the original, 28 Years Later drops Netflix viewers into a world of infection, survival, and the human stories hiding in the chaos.

When 28 Years Later hit theaters in June, fans of Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) and 28 Weeks Later (2007) were curious if the franchise still had something to say. With its Netflix release on Sept. 20, the film is reaching a wider audience and sparking debate over whether it lives up to its legacy.

Boyle doesn’t recycle old characters or storylines. Instead, he drops us back into the Rage Virus wasteland with a more intimate, character-driven tale. This isn’t about the collapse of society so much as it is about what it means to cling to family, identity, and sanity when the world has already burned down.

The Movie Plot

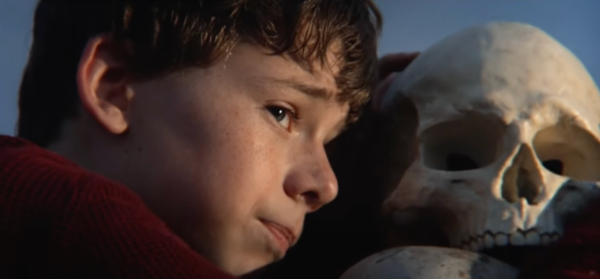

The spotlight falls on Spike (Alfie Williams), a preteen living with his parents (Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Jodie Comer) and a small community on a tidal island off England’s northern coast. The illusion of safety never lasts—the infected are just across the channel, and each low tide exposes a fleeting bridge back to danger.

The story kicks off when Spike joins his father on a rite-of-passage trip to the mainland.

Almost immediately, a chilling voiceover of Kipling’s Boots plays over eerie forest shots and wartime marching footage, the narrator growing more unhinged with every repeat.

Barely 15 minutes in, the message is clear—there’s no waking up from this reality. The characters must adapt, and slowly going “mad,” as the poem suggests, is the cost of enduring life in this world.

On the mainland, the film delivers both dread and spectacle. The forests are lush and calm, but the beauty collides with the grotesque reality around them.

The “slow lows”—bloated, crawling infected—blend into the undergrowth like twisted wildlife.

When Spike’s father guides him to line up a shot with his bow, it feels almost like a hunting lesson. Spike fires, but his hesitation is clear.

A second slow low, nearly missed, creeps up from out of sight—a stark reminder of how unforgiving this world is.

Their uneasy bond is tested again when faster, smarter infected, led by an alpha on a hill, ambush them. A tense chase forces them to hide overnight in an attic, where Spike spots a distant fire.

When Spike asks about the fire, his father dismisses it, leaving him uneasy. By morning, they barely escape an alpha at the village gates. Suddenly, the scene cuts to a celebration in Spike’s honor.

His father, drunk, brags about his bravery, while Spike awkwardly corrects him. The exaggerations aren’t pride but a way of coping—yet they push the two further apart.

That wedge breaks completely when Spike learns the fire came from a reclusive doctor. Furious that his father hid this from him, Spike threatens him to stay away from both him and his ailing mother, Isla. Convinced the doctor might help, Spike sneaks Isla off the island.

This second journey mirrors, but also contrasts, the first.

Unlike his coldly practical father, Isla balances vulnerability with fierce determination. Her illness leaves her regressing to childlike states, yet moments of clarity reveal strength and care. In one haunting scene, she kills an approaching slow-low at night while Spike sleeps, revealed only in a morning flashback.

In another, she assists a pregnant infected woman giving birth—miraculously, the baby is uninfected. Spike and Isla continue their journey, with the newborn in tow.

Their path leads to Dr. Kelson (Ralph Fiennes), the man behind the fire.

Far from mad, he’s eccentric but kind, having created a sanctuary marked by a monument of skulls and bones inscribed with memento mori—remember death.

Kelson diagnoses Isla with terminal cancer.

In a heartbreaking line, she admits her illness has shifted from “waves” to a tide she can no longer resist. Choosing her own terms, she asks for peace rather than prolongation.

Kelson honors her request, giving Spike her skull and inviting him to place it on the monument facing the sunrise.

The scene is grotesque and tender at once—a fragile but meaningful farewell in a broken world.

By the end, Spike proves more like his mother than his father, clinging to kindness and humanity.

After delivering the newborn and naming her Isla, Spike leaves a letter to his father—saying goodbye not just to him, but to his childhood.

With his mother gone, the last trace of innocence dies too, and he chooses to return to the wasteland to find himself.

My Opinion

I finished 28 Years Later thinking two things at once: it was beautifully made. Also, man, this is not the zombie movie I was waiting for. Don’t get me wrong, I love character-driven plots, and Boyle delivers raw performances and striking visuals.

The themes of family, survival, and sanity hit hard, and there are moments that stick. But the best zombie movies do more than move you—they unsettle you. They make you feel like this nightmare could spill into real life at any moment.

That’s the magic of the genre: one lab mistake, one viral mutation, one bad drug gone wrong. After COVID, that fear is sharper than ever. At its best, zombie cinema is a cocktail of dread, adrenaline, and emotional overload that keeps you on edge until the credits roll.

“28 Years Later” brushes up against that feeling but never really grips it the way the original did. It’s a solid film, but just an okay zombie movie. Still, with sequels in the works, maybe this one is only the warm-up round.

If Boyle leans fully into the terrifying, all-too-possible reality of a world wrecked by infection, the next installment could finally deliver the “zombie movie of the decade” I hoped for all along.